Browse through our Medical Journals...

Psychiatry in the CinemaEdited by Professor Ben Green

Schizophrenia |

||

SchizophreniaIn A Beautiful Mind (2002) Russell Crowe portrays real-life Nobel Prize-winning mathematician John Nash. He delivers a thoughtful, measured and moving performance directed by Ron Howard. Nash was a student in 1947 reading mathematics at Princeton University. He delivered a paper on game theory (the mathematics of competition) that overthrew the accepted ideas about economics, only for his mind to later succumb to what was then diagnosed as paranoid schizophrenia. Nash, with the considerable help and forbearance of wife Alicia (Jennifer Connolly), fought his disease and continued his mathematical work (still teaching even by the age of 73). He won the Nobel Prize in 1994. As a testament to the high heritability of schizophrenia his son, also a mathematician, reportedly had schizophrenia. The latter point is not mentioned in the film. Despite the romanticisation necessary to sell the movie to a studio and an audience, the film is reasonably realistic although it concentrates on visual hallucinations (rather than the more frequent auditory hallucinations of schizophrenia) for cinematic effect. Howard very prudently took pains to carefully research his film. He took advice from leading psychiatrists such as Professor Max Fink to avoid most errors that typically litter other directors' work on mental illness. Professor David, professor of neuropsychiatry at the Institute of Psychiatry reviewed the film (BMJ, Vol 324, 491) and comments on the psychopathology behind paranoid delusions. He links the success mathematical ability of Nash to the psychology of aberrant connections between events thus: "For someone who could produce mathematical formulae to explain apparently random behaviour and who could reduce human interaction to the rules of a game, it was a small step to seeing meaningful patterns in the random outpourings of newspapers and magazines - hidden messages from Soviet spies, warnings of Armageddon." The psychiatrist in the film, Dr Rosen (played by Chistopher Plummer) delivers the standard treatment of the day - insulin shock therapy combined with antipsychotics. The insulin shock therapy looks horrific with ten weeks of therapy with five treatments per week. According to the film insulin is administered intramuscularly and the resulting hypoglycaemia is allowed to induce bilateral convulsions. This is not quite what I had understood insulin therapy to be. Elsewhere in these pages is an account of insulin coma therapy by the contemporaneous UK doyen of physical treatments, Dr William Sargant. In his book the fits are a 'complication' of treatment i.e. an unwanted side effect. In the film the precise nature of the oral treatment for schizophrenia is not mentioned although two kinds of tablets, presumably an antipsychotic (perhaps chlorpromazine marketed in the US as thorazine) and an antiparkinsonian drug are seen to be administered. After release from hospital the side effects of the drugs (fogging of his mathematical mind and sexual side effects) lead Nash to stop compliance. His relapse is described with the recurrence of paranoid delusions about the Cold War and the vivid reappearance of visual and auditory hallucinations. Nash's hallucinations are remarkably consistent in form through the years of his illness and Rosen deduces that some of his college colleagues (such as a biology stduent room-mate seen earlier in the film) were in fact hallucinatory in nature. Thus Nash is accompanied in the film by a trio of halucinatory characters that never quite leave him - a CIA supervisor, his college room-mate and a little girl who is his room-mate's niece. There is one very scary moment in the film where his insight is so impaired off medication that his ability to parent is dangerously diminished. He is looking after his son is in the bath. The water is running and whilst Nash believes that his ex-room-mate is looking after his son he wanders elsewhere in the house. The waters rise and only the intervention of his wife prevents tragedy. Nash eventually complies with treatment although the main hallucinations never quite leave him. Nevertheless the antipsychotics do enable him to function, teach and have insight into what is real and what is not. Without that there would be no film. 'Proof' (2005) is not exactly a sequel to A Beautiful Mind (2002), but does I found the film curiously unengaging and 'flat', although colleagues have been more enthusiastic. However, the illness deals well with the impact of mental illness on carers and establishes how friends and family can be at once a source of support and stress to the sufferer. It is not cluttered with diagnostic labels and (unless I blinked) does not include any depictions of psychiatrists or mental health professionals.

Rather less comforting is Through a Glass, Darkly, the 1961 film by Ingmar Bergman. The film comes from an era when schizophrenia was seen as a 'functional illness' - an era when R.D. Laing and others pointed to the Family as the cause of mental illness. In this film the analysis of the family concerns the girl's relationship with her father, a writer who is "using" his daughters illness for "artistic inspiration". The film, set on a bleak island and filmed in black and white, does not sink into sentimentality or melodrama and provides us with some insight into the aetiology of a condition that even now is not fully understood. At the end of the film the girl is taken away to the mainland to be "cured", but it is difficult to imagine a happy ending because the unrelenting pessimistic atmosphere of the whole film has, by this time, affected everybody watching it. From the same liberal era when schizophrenia was 'functional' not 'organic' came the 1971 film by Ken Loach, Family Life. It again shows the Family as being responsible for the mental collapse of a sensitive young girl. The film is, like all of Loach's work, shot in a very realistic, almost documentary style which serves to try and convince us that these people are real and not fictional creations. The film is based on a play entitled In Two Minds, which was televised in the Sixties, causing some controversy in its condemnation of the parental figures. The film version is more effective because of its direction and the acting of Sandy Ratcliffe (as the girl) and Grace Cave ( as her mother ). The final scene, depicting a group of doctors and psychiatrists discussing the girl is very unsettling in its almost casual atmosphere. Highly recommended. Anthony Page's I Never Promised you a Rose Garden is a 1977 film taken from Hannah Green's book, which has a reputation for being one of the most effective descriptions of schizophrenia. The film version also has much to recommend it, not least being the central performances of Kathleen Quinlan (as a 16 year old girl struggling to distinguish between fantasy/reality) and Bibi Andersson (as the doctor who tries to communicate with her). There are some convincing portrayals of other female asylum inmates, plus some brilliantly directed sequences of life in a psychiatric institution. Roman Polanski directed Repulsion in 1964, a London-based film that introduced him to the English speaking cinema. He directed Catherine Denueve as a beautiful, but sexually avoidant young woman, Carol. Living in her sister Helen's flat she works by day as a manicurist in beauty salon. Her beauty attracts, but she is appears unable to cope with their advances and unsure of her own desires. At best she is ambivalent towards males. A final scene focuses on a family photograph in which Carol as a young girl is eyeing her father with vengeful eyes. One could speculate on the origins of her discomfort with her own sexuality and whether she is a survivor of sexual abuse.

What are we to make of Fight Club (David Fincher, 1999)? On the surface it is a film about male aggression and male discontentment with today's society. It could be a seen about a violent reaction to the emasculation of modern day man. This was very much how the trailers portrayed the film. The twists in the film however reveal that the main protagonist hallucinates his way through the film, inventing and interacting with the other main character (Tyler Durden) played by Brad Pitt. The film does not pretend to be a portrayal of paranoid schizophrenia and yet this could be the only explanation for the bizarre behaviour of Edward Norton's character. It could also be contended that the civil disobedience group created by Edward Norton's character could be seen as a mass induced psychosis - folie a deux on a massive scale. |

||

Black Swan (directed by Aronofsky, 2011) is a tale of a new production of the traditional ballet Swan Lake and the personal conflicts suffered by its young star Nina, (played by Natalie Portman), as she struggles to dance both the perfect and virginal white swan and the erotically charged, deceitful black swan. The desire to be perfection itself and the rejection of her burgeoning sexuality are fostered by her mother (played by Barbara Hershey) who suppresses her daughter’s development by smothering her in an exclusively close dyad where it is made clear she has over-invested in her daughter’s career in place of her own. The scene is set for a massive internal psychic conflict for which manifests as bulimic vomiting in toilets everywhere followed by some violent affect driven illusions where paintings move and shadows threaten. The film rushes through a gamut of eating disorder psychopathology and explores the symbolic and actual nature of deliberate self harm, boundary violations, domestic violence and blood itself. Towards the end the star hallucinates a murder of her rival, which may represent a stress induced psychosis, perhaps fuelled by drugs surreptitiously adminstred by her rival/friend. At times the visuals threaten to descend into the worst of grand-guignol, but overall the film is something of a triumph and food for therapeutic discussion. |

Affective Disorder

Vincent Van Gogh seems to have had episodes of psychotic depression, although it is difficult to retrospectively allocate contemporary diagnoses. Some writers have wondered whether Van Gogh suffered from bipolar affective disorder or even an organic disorder such as porphyria, These two films, Pialat's Van Gogh (1992) and Cox's 1989 film Vincent (The Life and Death of Van Gogh) are two of the most recent attempts to portray the tortured artist's life. Felix Post, Prof. Emeritus at the Institute of Psychiatry postulated that Van Gogh suffered from absinthe misuse and affective disorder. (Post F. Creativity and psychopathology. A study of 291 world-famous men. British Journal of Psychiatry. 165(2):22-34, 1994 Jul.

In The Snake Pit (1948 directed by Anatole Litvak), Olivia deHaviland (as Mrs Cunningham) portrays a woman with a depressive psychosis and amnesia. The fim revolves around her past relationships with her husband, mother and boyfriend. Ambivalent feeings about her father and boyfriend are followed by their deaths and a subsequent guiity feleing that she is unable to (or should not) love. This results in problems with her later relationship with husband Robert and a lengthy admission to a State Hospital. There is a quite brilliant evocation of the 1940s State Hospital system with a rounded portrayal of the psychiatric system.There are depictions of psychotherapy, electroshock and narcosynthesis. The state hospital is burdened by more than twice the number of patients than it was designed for (718 patients compared with 312) and the stress on staff is evident with nursing staff themselves becoming mentally ill. A hierarchy of wards is depicted with the aim bing a progress up through the numbers towards ward one from which discharge can ocur. At one point Mrs Cunningham falls fou of the bitter nurse in charge of ward one and is pummeted down the hellish ward 33 (the Snake Pit of the title). Here there are very good depicitions of mania, sterotypies and thought disorder. The film stands up fairly well to the passage of time and the viewer has the sense that the depiction of the 1940s hospital system is fairly accurate, especially when viewed alongside asylum footage from contemporary documentaries. |

||

Organic Disorders

Iris (2001) depicted the true story of the decline of author Iris Murdoch. Murdoch's husband wrote the book on which the film is based and so the account is practically an eye witness account of the tragic effects of dementia on a brilliant mind and in turn the effects on her husband/carer.

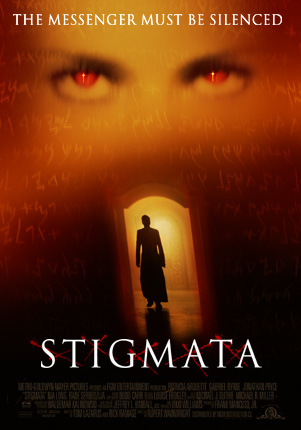

Rupert Wainwright's 1999 film Stigmata featuring Patricia Arquette features an intriguing story of a young hairdresser/body artist who develops four of the five stigmata - lesions on her wrists, feet and forehead. The film eventually settles on a supernatural explanation, but not before involving doctors in a medical quest to construct a differential,diagnosis which included Borderline personality disorder, self-cutting, deliberate self-harm, and epilepsy. For while the film runs with the idea that Arquette's character, Frankie Paige, has convulsions and visual hallucinations and this necessitates a round CT/MRI scans and a fearsome sounding EEG involving electrodes 'inserted into the neocortex', a very dramatic investigation! EEG electrodes are most usually applied to the scalp. There are parallels with the CT investigations of the girl in The Exorcist (1973), after her supposed auditory hallucinations. In another parallel between the two films, the investigator following the story through is a priest. In The Exorcist it is a psychiatrist/priest. In Stigmata it is an organic scientist /priest. Both have doubts about their scientific and religious vocations. At an artistic level Stigmata is a visually beautiful film with glorious symbolic treatments of water, blood and the Madonna/Whore. The score including songs by the Smashing Pumpkin's Billy Corgan, Sinead O'Connor, David Bowie and Bjork is also a sumptuous treat. Hytner's 1994 film The Madness of King George is a fair rendition of Alan Bennett's play which depicts the decline of George III into an organic psychosis. Bennett's play strongly implies that George III suffered from the effects of acute intermittent porphyria. Oliver Sacks' books on the psychiatric aspects of neurology make good reading. Awakenings is Penny William's 1990 film of Sack's first bestseller. The film gives an account of middle aged and elderly patients incarcerated by a lifelong illness. The illness is portrayed as a chronic catatonic state triggered during the early 20th century influenza outbreak: so-called encephalitis lethargica. The Awakenings that the title refers to are the returns to consciousness that the patients wake after Sacks (played by Robin Williams) administers a new drug . Sadly the effects are short-lived and the victims return to their twilight state. Interestingly this is not William's only foray into playing physicians. He plays a consultant psychotherapist in Good Will Hunting and makes a convincing one, but in the film Patch Adams, although based on a true story he seems altogether more unlikely. Harrison Ford plays a successful and driven lawyer in a 1991 film directed by Mike Nichols. In Regarding Henry Ford suffers from amnestic syndrome and has to re-evaluate his private and professional life. |

||

The Psychiatry SystemThe major film in this sub-genre has to be Milos Forman's 1975 film One Flew over the Cuckoo's Nest starring Jack Nicholson. I saw the film twice - at the beginning of my career as a student doctor and again after a gap of two years as a consultant psychiatrist. My impressions of the film had completely altered with my standpoint. At one point I thought Nicholson the victim of an oppressive madness machine and at the other point I saw him as a disruptive personality disorder who mocked and abused the system.

Instinct (1999) was directed by John Turtletaub and features Anthony Hopkins who seems to have developed a recent predilection for playing psychotic doctors. In this case it is not the (supposedly criminally insane) Dr Hannibal Lecter but an anthropologist, Ethan Powell, who has undergone trauma whilst observing gorillas in the field. The anthropologist is put into a state hospital for the criminally insane - which resembles the crumbling environment of the brilliant sixties US documentary Titicut Follies about such a hospital in Massachusetts. The abusive system of the total institution makes Hopkins' character observe that his fellow man is worth less than the gorillas he befriended in the wild. He is seen as a special patient and a catch by the psychiatrists because he is a case of elective mutism. Powell's assigned psychiatrist is played by Cuba Gooding Jr. and initially sees Powell as someone who will help his career in that his case might generate a publication or two. Donald Sutherland features as a creatively psychopathic Professor of psychiatry who counsels his junior and mentors his career. The film is about freedom and morality and although Ethan Powell longs for freedom, he sees himself as less trapped than his psychiatrist, enmeshed in a system of patronage and required behaviour. Having seen The Silence of the Lambs it is difficult to separate the characters played by Anthony Hopkins in both films. Instinct provides an interesting comment on psychiatry and a counterpoint to Silence of the Lambs and Hannibal.

Shutter IslandShutter Island (2010) is director Martin Scorsese’s take on the gothic asylum horror film. It has visual quotes from other asylum films like Gothika (lightning bursts), Titicut Follies (depiction of inhumane militaristic care), and The Snake Pit (depiction of sociology/stigmatisation). Unlike many 20th century films about mental illness in this 21st century film there is no optimism about he advent of new psychotherapeutic methods (compared to say The Snake Pit). This is a bleak vision of mental illness where the illness equals danger and incurablilty and the patient equals monster. No-one could accuse Scorsese of having a liberal agenda. The fort-ike asylum of Shutter Island merely suggests the containment of violence and the main character (Leonardo di Caprio) asserts that the mentally ill offender deserves no ‘calm.’ The story revolves around a rare and precious opportunity on the island to see if psychotherapy, not drugs, can penetrate the defences of a insightless traumatised survivor of WWII who has liberated the concentration camp of Dachau and murdered his bipolar wife in revenge for her killing of his three children. It’s a bleak complex plot that is as paranoid as it gets. It melds together twists about Nazis, communists, Hoover’s CIA, LSD mind experiments, and the Institution – this takes some doing. The result is a success, but only just. The film’s plot just about avoids some plot loopholes, but is overwrought, bloody and so graphic as to leave some audience members laughing nervously. It would be improved by judicious editing to rein in the gore. This is a distinct case of a film where the 'less would be more'. Over the course of the plot various character arcs and twists take the lead psychiatrist (Ben Kingsley) from evil mastermind genius (in audience eyes) to fallible, altruistic, heroic psychotherapist. His vision argues against the new drugs – chlorpromazine – and psychosurgery (lobotomy). The arc of German psychiatrist (Max von Sydow) is from Nazi experimenter to pragmatic psychosurgeon. The lead character’s arc is from Federal agent to paranoid PTSD sufferer – with flashbacks, nightmares and a drink problem. Kingsley’s psychiatrist is shown to fail and I wondered if this film sounds a 21st century retreat from optimism about CBT, Psychotherapy etc and a much more cynical, sceptical view of the mentally ill. It’s a well made, carefully thought out film with good period detail. Those who have worked in total institutions (a la Goffman) will recognise the asylum of Shutter Island with its tension between the sometimes opposing aims of care and security. Despite all his however the target audience of this film will go away from the cinema with even less sympathy for people with mental illness. |

Personality Disorders

There are numerous films that depict main characters with sociopathic traits, controversially these characters are often 'heroes'. For instance if we consider any of the James Bond films - these involve a main character who is disturbingly glib about the people he kills (and he kills again and again). He shows virtually no remorse and although he can easily form relationships with women, these demonstrably do not last. True depictions of other personality disorders are rare. True personality disorders probably do not make good film material. Schizoid individuals (without friends and lovers) would form the basis of a very tedious film. Jack Nicholson's 1997 portrayal of an obsessional and isolated US romantic novelist in As Good as it Gets (directed by James L Brooks) makes a fascinating comedy. His lifelong disorder probably represents an anankastic personality disorder rather than an episode of obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). Borderline personality disorder is represented in Girl, Interrupted James Mangold's 2000 film showing how a young girl is admitted to a psychiatric ward after being sectioned by a psychiatrist she only met once. The diagnosis (based on her earlier depression and attempted suicide ) described her as having borderline personality disorder - this led to her being kept against her will and medicated until the authorities decided she was once more able to integrate with society. During her incarceration she befriended other girls in the institution and made her first steps towards becoming a writer. Later her experiences are published and acclaimed. The hospital sequences portray the institution as old-style asylum however not dissimilar from the hospital in One Flew over the Cuckoo's Nest or Terry Gilliam's Twelve Monkeys.

|

||

Learning DisabilityDustin Hoffman portrays an adult (Raymond) with autism in Rain Man (1988) who has been effectively institutionalised. His brother, Charlie, a car salesman (Tom Cruise) realises that he has this autistic brother only after his father dies. Because Raymond has inherited the bulk of a fortune, Charlie effectively kidnaps him and exposes Raymond to the outside world with life changing results for both of them. Hoffman's portrayal shows the conservative and obsessional features of the disorder together with the 'islands' of extraordinary ability sometimes seen in autistic sufferers. In this case Raymond's skills are mathematical. |

||

Neurotic DisordersIt would be possible to classify some films in several categories, because some depictions of mental illness do not neatly fit into a recognisable psychiatric classificatory system. That is to say the apparent diagnoses of some characters have symptoms drawn from several disorders and melded into an interesting mosaic. The patient portrayed by Kevin Spacey in K-Pax (2001) is a case in point. There is the possibility that he is grossly deluded (because he is absolutely convinced that he is an alien called Prot). There is also the possibility that he has a hysterical amnesia brought on by the murder of his immediate family. The former symptom (a grandiose delusion) would imply a psychotic disorder and the latter some form of neurosis. The film also teases the viewer with the possibility that Prot is actually an alien and he is able to give various astrophysicists a run for their money as he describes exactly where his solar system might be in the night sky. They are almost convinced and so is his psychiatrist Dr Powell, convincingly played by Jeff Bridges. Dr Powell's keen attachment to his work produces some alienation from his own wife and family which is a nicely observed counterpoint and will be a familiar theme to many doctor's families. Jacob's Ladder (1990) directed by Adrian Lyne and written by Bruce Joel Rubin could be summarised in psychiatric terms as 'PTSD or not PTSD' . The hero, Jacob Singer (played by Tim Robbins), appears to be a survivor of the Vietnam war. There are graphic scenes (earning an 18 certificate in the UK) depicting his war traumas in which his platoon is destroyed and he is bayoneted in the stomach. The next portion of the film describes his new life as a divorced postal worker, living with a new woman, Jezebel. He suffers with recurrent nightmares derived from his experiences, seems hypervigilant, has flashbacks during the day, is irritable and distant from others and in many ways is a classic case of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). The memory of his dead son, (acted by a very young Macaulay Culkin) haunts him, and these include horrid images of his son being run over. The literal interpretation of Vietnam PTSD is thrown into disarray however by other levels within the plot. A psychic at a party hints that Jacob's palm shows he is already dead. His chiropractor has an angelic quality. He and his Vietnam compatriots feel that they have been experimented on. Jacob's paranoid imaginings become reality as his psychiatrist is exploded in a car and a fellow vet with similar symptoms suffers the same fate. There are allusions to demons and witchcraft and a variety of other 'red herrings'. The last scenes suggest that Jacob has been, as the palmist at the party suggested, dead all through the film. In some ways Jacob's Ladder prefigures the 1999 film The Sixth Sense, (reviewed below). His presence is as some ghost or lost soul attached to the earth by his personal demons. Once he begins to 'let go' as his healer/chiropractor Louis suggests, he can leave the earth. One of the final scenes sees Singer climbing the stairs towards a brilliant light, his hand being held by his dead son, who in Jungian terms might just symbolise the puer aeternus. It is a moving film with some disturbing imagery, but ultimately inspired by a more hopeful spiritual philosophy- a kind of afterlife psychotherapy movie! |

||

Child PsychiatryThe 1999 film Sixth Sense, directed by M. Night Shyamalan, is a superior ghost story starring Bruce Willis and with a compelling performance by child actor Joel Osment. Willis puts in a surprisingly sensitive performance as a leading Child Psychologist with an apparently failing marriage. He tries to help a young boy who is troubled by visual hallucinations, which in the story are actually ghosts of people who need help from him. The child is, in effect a medium, and being approached by troubled spirits for help. Why is it good? Well, the therapeutic relationship between Willis and the boy is touchingly portrayed and the twist at the end is genuinely surprising. I suppose the film best shows the importance of gaining a therapeutic alliance with child patients. Virgin Suicides (1999) directed by Sofia Coppola and starring James Woods and Kathleen Turner is a story is based on the suicides of five girls belonging to a strict religious North American couple. The film was almost universally panned by the critics and yet is a poignant and well-observed account of an almost unbearable tragedy. Woods plays a passive father to Turner's strongly religious mother. Turner's mother effectively suppresses her very beautiful daughters' blossoming sexuality and closets them from the outside world. The psychiatrist in the film describes the suicidal gestures of the first daughter as a 'cry for help' perhaps showing the risks inherent in this kind of labeling of self-injurious behaviour. As to why the film was disliked by the critics? Well the subject is an inherently unpleasant one, although Coppola does treat it with some nice ironic flourishes, but the suicides appear fundamentally non-understandable - which is their very nature - and I suppose that this is what the critics could not adjust themselves to, rather than the film itself. The soundtrack, by Air, is pleasant and dreamy. |

||

Negative Images of PatientsA special mention is very much deserved for Me, Myself and Irene (2000). This film was directed by the Farelly brothers, who also concocted depictions of excess in such films as There's Something about Mary (1998). Its depiction of a policeman with schizophrenia, played by Jim Carrey, is almost entirely devoid of accuracy, sensitivity and subtlety. His behaviour is clownish, obscene, violent and sexually assaultative. He is referred to as 'schizo' and 'psycho'. It was criticised by SANE Australia, the US National Alliance for Mental Illness and the UK Royal College of Psychiatrists amongst other organisations. |

||

Negative Images of PsychiatryPsychiatric professionals in films have been venerated, demonised or marginalised according to Schneider who terms these individuals, respectively, "Dr Wonderful", "Dr Evil" and "Dr Dippy" (Am J Psychiatry 1987; 144: 996-1002). Wonderful PsychiatristsThe depiction of psychiatrists as anything near desirable role models in film are few and far between. In the under-rated Mesmer (1994), Alan Rickman portrays Dr Franz Anton Mesmer who, although not a psychiatrist, according to the film at least, trailblazed a path for considering the psychology of the human condition. His contemporary physicians see themsleves as men of science and scoff at the good Dr Mesmer and his healing via animal magnetism. Dennis Potter's script though sees Mesmer as a foreshadowing of Sigmund Freud, beginning to scent out the true causes of hysteria in the seemingly much afflicted Vienna. Mesmer begins to cure a young, abused, woman of her hysterical blindness in the film. Whether this is a mere byproduct of his removing her from the incestuous advinces of her father or due to his sensing a glimmer of her psychology is another matter. Although his 'animal magnetism' is portrayed as a failure Mesmer is designed to be seen in this film as a man of intellect and feeling who can see the need of the mind for healingand balancing rather than enduring what science can offer (bleeding and purges). Admittedly science in those days could offer little... Unfortunately Mesmer fails to foresee an re-enactment of the abuse and gets his doctor-patient relationships all messed up, rather as Freud would himself in his early strugggles to understand transference. Rickman's acting is sympathetic and thoughtful and he is clearly baffled by the virulence of the medical establishments' attacks on his methods.Watch the film an play 'spot the villain' - inadvertently abusive Mesmer, deliberately abusive fathers, or self-interested Viennese doctors? The film is based on a script by the much-lauded Dennis Potter , directed by Roger Spottiswood and had original music by Michale Nyman. With the talent involved the film should be predicted work, but somehow the film doesn't quite. Is it the rather leaden editing? Evil PsychiatristsThe monochrome German Expressionist film, Das Kabinett des Doktor Caligari, (1919), directed by Robert Wiene, represents a cinematic first - the first true horror film and probably the first film to depict psychiatrists, their patients and an asylum. The stereotype of the mad or evil psychiatrist is therefore the precursor of all other depictions.Dr Caligari is an 18th century hypnotist who is supposedly admired by the director of a German lunatic asylum. Caligari used patients (somnambulists) to carry out a series of murders. The director so idolises Caligari that he wishes to become him, and wehna somnambulistic patient is admitted to the asylum the director seizes the opportunity to become his idol. The director becomes so excited by his fantasies that he appears to hallucinate. Readers will appreciate that this is difficult enough for today's film makers to portray accurately. How do you convey hallucinations in a silent black and white film? The ingenious solution is to have the director surrounded by sentences written on the frame that flicker on and off around him. The effect works. The sentences include "Du mußt Caligari werden". Swayed by these second person auditory hallucinations or command hallucinations. The asylum director( played by Werner Krauss) becomes Caligari, assuming his shadow side, and travels around with Cesare (the somnambulist) and through him kills people at night. Rather like Dr Lecter, decades later, the Director's motives for murder are sometimes as flimsy as someone being rude to him! The town clerk angrliy asks Caligari to wait when he asks for a permit. This is sufficient cause for Caligari to send the somnambulist Cesare to kill the clerk late at night.

The exact diagnosis of the somnambulist is difficult to ascertain. It is certainly not a diagnostic entity seen today in psychiatric practice. The closest diagnosis might be a variant of catatonic schizophrenia - itself very rare nowadays. Catatonia would have been more prevalent in 1919 though, before the advent of antipsychotic drugs. Caligari is hunted down by the police after they rumble his fake circus act with Cesare. He runs for his life back to the asylum where he reassumes his identity of respected asylum director. In a twist, the story is told by a third person, Francis. He is revealed to be a patient in the asylum at the end of the film, and thus 'normality' is restored as the audience can deduce that the murderous Caligari is nothing more than a paranoid delusion of a patient about the Director. In When the Clouds Roll By (1919) psychiatrist Herbert Grimwood attempts to drive Douglas Fairbanks to suicide. In this, one of the first screen psychiatrists, the "mind doctor" turns out to be an escaped lunatic. One of the most evil of screen psychiatrists must surely be Hannibal Lecter as played by in Silence of the Lambs (1991) . Lecter is the serial killing cannibal in a mask, stored in a maximum security mental institution. In a way this is a play on the 'madder than the patients' theme. Lecter first surfaced in Manhunter (1986), played by Brian Cox. The film enjoyed moderate success, and Cox's portrayal of Lecter is more than adequate. Some critics rate this film as the best of the three made to date. In two films which followed Hannibal the Cannibal was definitively played by Sir Anthony Hopkins. A remake of Manhunter is planned with Hopkins in the lead.

It matters because the Hannibal series of novels and films depict something at once simple and archetypal, but at the same time quite complex in terms of internal reaction. And it is society's acceptance of Hannibal as a character and, furthermore, as a hero that is of particular interest. The broadest stroke of the films speaks volumes about the demonic and fearful nature of mental illness within our collective mind. Aliens (as they used to be called) and their alienists are grouped together as beyond reality and on the whole nightmarish characters. My judgement is partial, of course, since I am a psychiatrist. I was asked by the Headline publishing house to comment on the second novel in the sequence, The Silence of the Lambs. Plans were then in discussion to publish a sequence of novels by yours truly featuring a realistic and recognisable psychiatrist as hero. The sequence was never published, but the novels still exist, slowly mustering dust and unread somewhere. My bone of contention with the second novel's Lecter character was his psychopathy and lack of remorse and yet his finely attuned, almost prescient sensitivity to the psyche of others. This, I argued was an unlikely combination of personality traits in a doctor. I also had some problems with minor technical points such as Lecter's ignorance of DSM diagnostic terms, but this was merely hair splitting stuff. I just thought that a serial murderer doctor was bizarre and incredibly unlikely. This opinion, of course, was proved wrong. As I was opining to Headline, Dr Shipman was working singlehandedly down the road from where I live dispatching far more people than ever written about in the gothic pages of Thomas Harris. The hoary adage that truth is stranger than fiction was sadly proved right again. So, why do we at the same time like Dr Lecter and also feel repelled by him? We somehow will to him to survive and continue, but we abhor his atrocities, even if they are executed with murderous skill and an eye to the artistic. The uncomfortable truth is that Lecter is our Shadow - this true of and uncomfortable for all of us, but especially for psychiatrists who might identify with him even more closely. The Shadow lies within us, [our dark side as portrayed in the Star Wars series - which George Lucas based on the archetypal books and research of , itself based on the writings of Carl Gustav Jung - an example of how psychiatry has sometimes had a reciprocal role with cinema] and we must integrate our own dark impulses with our 'ideal self'. Perhaps the identification process with Hannibal is akin to a form of Stockholm syndrome in which the victim, after prolonged exposure to the aggressor, eventually identifies with him. Or is there something very dark and murderous within each of us? Is this what is truly disquieting about the heady archetypal brew that is the Hannibal series? One of Ridley Scott's most brilliant aspects as a director is his use of lighting and shadow in his films. His previous films include Alien (1979) and Bladerunner (1982). Hannibal makes great use of the light and dark in the key scenes set in Florence. Sunny scenes of Hannibal living the life of a bon viveur and gastronome alternate with dark rainy streets scenes where he murders a gypsy and the policeman Pazzi. When he first attacks Pazzi it is in the art museum/library where Hannibal is hiding out as a curator. Lecter has just delivered a seminal lecture, he projects a slide showing the execution of one of Pazzi's ancestor's, and as he does so he advances on Pazzi. His shadow towers above Pazzi on the screen as Lecter moves forward in the projector's light to drug him. Pazzi is murdered because he has sold Lecter for a considerable reward. Lecter reminds Pazzi before his death that an ancestor was killed for a similar betrayal. In this way Lecter justifies his murderous actions. Pazzi is stained with the sins of his ancestors, with Original Sin? The parallel of course as far as Pazzi is concerned is with Judas, but is Lecter in anyway a Christ-like figure? The novel is more complex than the film, and in a way this is understandable, some of the concepts put forward in the book would be difficult to translate for the screen. For instance, Lecter takes refuge in his Mind Palace, an exquisite architectural edifice that exists in his mind alone, and in which he place imaginary objects to fortify himself 'spiritually' and also to help him arrange his memory. Differences between the novel and the film include minor details such as Lecter's preferences in terms of musical instruments and major factors such as whole sections devoted to the psychodynamic aspects of Lecter and the detective Starling's childhood, and the romance between the female Starling and the male Lecter (an echo of Beauty and the Beast). In the novel Lecter plays the harpsichord and the theremin (an early kind of electronic instrument from the mid twentieth century where the movement of the hands in space produces an unearthly wailing sound - you will have heard music including a theremin, but perhaps not realised it) and in the film he plays the more accessible pianoforte. In the novel there is considerable space devoted to Lecter's early childhood relationship with his sister. She dies in a wartime atrocity, and the seeds for Lecter's negation and his transference to Starling are sown. The film excludes these psychodynamic explanations (inserted late in the day in the Hannibal series of books). The scenes in which Lecter tries to help Starling psychologically by unearthing literally (not figuratively in psychotherapy) the bones of her late father have also been omitted in the film. In the novel, the relationship between Starling and Lecter develops (at times ambiguously) into a romance. Readers did protest at this development, pointing out that Starling would not blur boundaries in this way, and the film portrays her as a sterling, straight officer of the law, albeit with a grudging respect or even affection for Lecter. In the film, although she is drugged, it seems clear that she has formed and close affective bond with Lecter who take her to the opera and so on, with her turning her back effectively on the FBI and her past. The novel implies that her role in the police is a defence mechanism linked in to the complex about her father. In undoing this Lecter frees her and the way is open for her to leave the neurotic attachment to the police and begin romance with Lecter. Would Jung approve of this 'coniunctio' between the anima and animus? Something doesn't feel quite right, and the movie perhaps because of this emotional dissonance rejects this subplot. Gone too is some of Harris' atheistic polemic. He denies God several times in the book and this post-Millennial fare implies that mankind has gone beyond good and evil in a Nietzchian way. Lecter is some cannibalistic monster who devours his victims, absorbing their thoughts, souls and bodies like some black hole absorbing surrounding stars. It is a dreadful Universe. If any body is in charge instead of God in Harris' Universe it is some dreadful Sethian demiurge who allows atrocities to happen and recur (the death of Lecter's sister is repeated figuratively in his murders or tableaux). It is a bleak and frightening universe offered by Harris. A weltanschaung that is even more frightening that Lecter, who is surprisingly a hero. His murders do ahev some logic or ethical basis. His asylum nurse Barney points out (in book and film) that Lecter only murders 'the rude', the inconsiderates, and the devious Judas like figures represented by Pazzi. The sentence of death for rudeness seems rather disproportionate however, and in the end I am personally repelled by this warped and profoundly pessimistic philosophy. It is a world without God. The Shadow remains however. This is a very grim fairytale where good is conspicuously absent and evil plays freely. In the wake of the fictitious Hannibal and the reality of Shipman we are left bereft - where have the heroes gone? The image of the evil psychiatrist is presented even to the young. Disney Studio's Beauty and the Beast (1991) features an evil asylum psychiatrist. The psychiatrist is bribed by the heroine Belle's suitor Gaston to incarcerate her father in the asylum. The planned incarceration would pave the way for Gaston to marry Belle. Sad to say, the bribed mad-doctor turns up at Belle's house to carry away her father in a lcoked carriage, accompanid by asylum heavies. Rather a negative image of mental illness, psychiatry and psychiatrists to peddle to the young.... Quills (2000) is a film about the Marquis de Sade, directed by Philip Kaufman. The film documents the incarceration of the Marquis de Sade, played by Geoffrey Rush, in a mental asylum in the 1790s. The asylum of Charenton's regime is under the supervision of a priest, (The Abbe du Coulmier). The milieu is intended to be therapeutic and incorporates the inmates' participation in a small amateur theatre. The film does not portray the Marquis as insane. He has comfortable private quarters, drinks wine and has easy access to books and writing materials, writing being seen by the Abbe as a cathartic therapy. The Marquis enjoys a privileged relationship with the priest in that he has ready access to him to discuss his treatment. The priest also has hopes of reforming the Marquis' body, mind and soul. The fly in the ointment comes when, in league with his publisher and aided by an asylum laundress Madeleine (Kate Winslet), the Marquis smuggles out another of his lurid fictions, a novel, Justine. The Emperor Napoleon is incensed. The incarceration has been designed to prevent the spread of the Marquis' sexual writings. The contemporary view of this incarceration could be that the State was attempting to censor de Sade and his sexual writings. For philosophical and medical reasons modern mental health legislation excludes out of the ordinary behaviours such as variant sexuality or substance abuse. The boundaries between insanity and sanity were presumably not so defined in Napoleonic France. The next point of interest is that the film documents the change of 'ownership' of the insane: from the soul-reforming institution run by the church to the scientific treatment asylum of the doctors. The Marquis' publication of erotic fiction crystallizes the change as far as the (institution's name) is concerned. A troubleshooting psychiatrist is appointed to reform the asylum and transform the Marquis' treatment. He is to be silenced. The psychiatrist, (Dr. Royer-Collard) is played by Michael Caine, who benefits financially from his new position and marries an underaged virginal orphan from an nunnery. At the same time as Caine mentally duels with the Marquis (who tries to smuggle out his writings on bedlinen and clothes) his new wife is reading the Marquis' work and becoming 'enlightened' or 'corrupted' depending on your point of view. Both psychiatrist and patient work in opposition. The battle for hearts and minds poetically leads to the destruction of the psychiatrist's marriage and the death of the Marquis. The psychiatrist lives on however, and the benign institution of the priest is gone forever. Dr. Royer-Collard is portrayed as unsympathetic and ill attuned to his patients, even using such brutal therapies such as an Iron Maiden. Such physical therapies seem barbaric now, and I have never personally heard of the Iron Maiden used, but there is plenty of documentation about the use of physical restraint and frantic attempts at providing alternative therapy such as magnetism, whirling chairs, wet blanket therapy are historical fact. The film also focuses on mental disorder at a time when it was relatively undifferentiated. The morass of mental illnesses would include schizophrenia, mania, dementia, acquired and congenital leaning disability and physical causes of insanity such as syphilis, alcoholism and environmental poisoning. Unsurprisingly Caine's medical regime emphasises behavioural control and containment rather than cure. There simply was none at the time.

In Gothika (2004) Dr Grey (Berry) wakes up in the selfsame women's penitentiary (where she works in the asylum wing) a few days after butchering her husband (also the chief psychiatrist of the asylum wing of the penitentiary). Is she mad? is she bad? Or is it just the script that's bad? Whereas Hannibal vs. psychiatry produced a 1-0 score with psychiatry scoring nil, the film Gothika (2004) yields an impressive 4-0 score. Gothika has a crop of four psychiatrists, none of whom is exactly a credit to the profession. Two are of the incompetent variety, variously denying or failing to understand the world around them. The other two are mad/psychic (Dr Miranda Grey played by Halle Berry) or downright evil abuser (Dr Douglas Grey - Charles Dutton). Dr Miranda Grey, strictly speaking, would fit under the category below (ill psychiatrists) because she suffers with a full range of delusions, hallucinations and thought disorder as diagnosed by her colleague Dr Graham (Robert Downey Jr). However as Hollywood would have it and (as any psychiatrist should know according to Hollywood anyway) such psychopathology is actually based on an accurate view of the world which should include ghosts, poltergeists and so on. As she says to Dr Incompetent : 'I'm not deluded, Pete, I'm possessed". Anyway Dr Miranda Grey's route to salvation lies in learning that psychiatry is not all it's made out to be and that listening to ghosts pays dividends - in this case getting her off a murder charge whilst she was possessed by the daughter of another psychiatrist (Dr Parsons as played by Bernard Hill). At times it's quite a scary and stylish film but as a medical specialty psychiatry is thoroughly rubbished in every possible way. Orthopaedics never gets this treatment! Ill Psychiatrists Mental illness is itself so frightening that perhaps it helps to fantasise about the healer being ill themselves. Films in this vein sometimes portray the 'mad psychiatrist' as funny which betrays the underlying prejudices of the film maker about mental illness. Maybe it seems more politically correct to mock the psychiatrist rather than the patient, but the joke is on those with illness nevertheless. Some 20 to 30 % of health workers have been shown to have anxiety or affective disorders and their condition is no more risible than their patients. Such 'comedies' are really only a a few steps removed from the public visits to Bedlam to mock the inmates. Ingmar Bergman could never be accused of making cheap shots or thoughtless comedies, in his masterpiece, Face to Face (1975) he sensitively explores the tragic irony of the psychiatrist suffering with mental illness. Liv Ullman plays a psychiatrist married to another psychiatrist; both are successful in their jobs but slowly, agonisingly, the wife succumbs to a breakdown. She is haunted by images and emotions from her past and eventually cannot function ,either as a wife, a doctor or an individual. The film is very long and inevitably harrowing, but it is a rewarding experience for the serious student of both cinema and psychiatry. Mel Brook's character in High Anxiety (1978) has a fear of heights which is used to parody Hitchcock's thriller Vertigo, as the entire film is a spoof of various Hitchock movies including The Birds and Spellbound as well. Brook's psychiatrist though might properly be seen as a comic character and would be an example of the next group, Funny psychiatrists.

Funny Psychiatrists In High Anxiety (1978) Mel Brooks plays Dr Thorndyke, a psychiatrist who is appointed medical superintendent of an hospital (the 'Psychoneurotic Institute for the Very, VERY Nervous'). Howard Morris, whom Thorndyke refers to as 'Professor Little Old Man', is the old man archetype to his protege Thorndyke. He analyses Thorndyke on the couch (again) to try and help him get a grip on his neurosis. The film is a loving pastiche of Hitchcock's work and also Hitchcock's forays into the world of psychoanalysis (e.g Spellbound). The parody of an American Psychiatric Association meeting within the film is particularly wry. A depiction of asylum politics with a battle for the envied position of medical superintendent is nicely done with the hierarchy providing motives for skulduggery and attempted murder. Paralleling the medical hierarchy is a nursing hierarchy headed by Nurse Diesel (Cloris Leachman) whose prune faced matron has an impenetrable accent and pointier breasts than Madonna. A lot of the jokes are so 'in' and so 'niche' that the film is not popularly seen as one of Brook's funniest. |

Notes: Stockholm Syndrome - in 1973, four hostages were taken in a flawed bank robbery at Kreditbanken in Stockholm, Sweden. At the end of their captivity, six days later, they actively resisted rescue. They refused to testify against their captors, raised money for their legal defence, and according to some reports one of the hostages eventually became engaged to one of her jailed captors.

Last amended March 2007- Copyright Priory Lodge Education Ltd 2001-2007

Thank you to Hanna Antony for her contribution to this page, Dr Stefán Steinsson, MRCPsych, Consultant Psychiatrist Iceland, for his suggestions and comments about Van Gogh and Regarding Henry, Dr Richard Hopkins MRCPsych, Consultant Psychiatrist UK for suggesting a look at Jacob's Ladder and Andre Suykerbuyk for suggesting Rain Man

Click

on these links to visit our Journals:

Psychiatry

On-Line

Dentistry On-Line | Vet

On-Line | Chest Medicine

On-Line

GP

On-Line | Pharmacy

On-Line | Anaesthesia

On-Line | Medicine

On-Line

Family Medical

Practice On-Line

Home • Journals • Search • Rules for Authors • Submit a Paper • Sponsor us

All pages in this site copyright ©Priory Lodge Education Ltd 1994-

"You can't trust somebody when they think you're crazy."

"You can't trust somebody when they think you're crazy."