Browse through our Journals...

Charles Dickens - an early case of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Ben Green

Critics of the diagnosis of PTSD state that it is a twentieth century concept, related primarily to an American compensation culture. However historical examples of PTSD pre-date the World and Vietnam Wars and the twentieth century compensation cultuire. Historical examples of PTSD have included Samuel Pepys, who had horrific dreams about the Great Fire of London in the seventeenth century. Here we will consider the historical evidence for the diagnosis in the author, Charles Dickens.

Charles Dickens (1812-1870), the most successful author of his day - an international traveller - then aged 53, was returning from a trip to Paris on 9th June 1865 . They were on a train to London. In the coach with him were his partner Ellen Ternan and her mother.

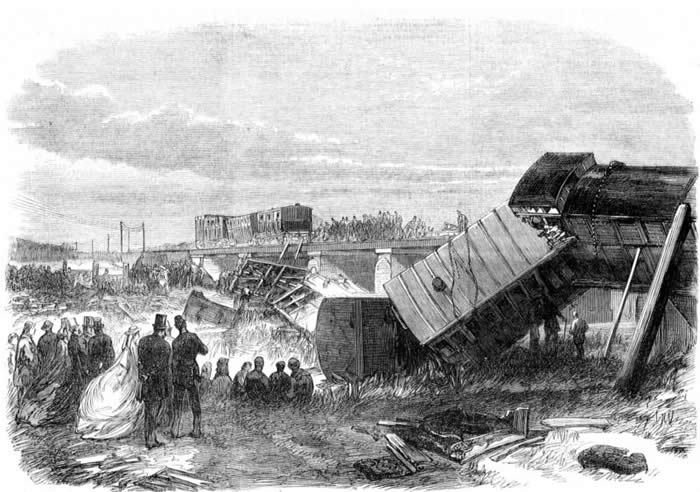

The train track was being repaired near Staplehurst in Kent. Part of the track over the bridge had been dismantled and a mistake had been made about when the express was due. The oncoming train was unaware that there was a gap of 42 feet long in the tracks over the bridge. At the last minute the engineer saw the situation, but it was far too late to stop. The engine and the first part of the train sped across the gap in the tracks, but the coaches in the centre and the rear of the train fell into the river bed below. Dickens' coach dangled from the bridge.

Dickens and Mrs. Ternan were physically uninjured. Ellen had only minor injuries. Others weren't as lucky. Ten people were killed and about fifty were injured.

Dickens scrambled from his coach, and using brandy froma flask adn water carreid from the river in his top hat did what he could to aid and comfort the injured. He described the scene as ‘unimaginable’.

He saw a dying man, still pinned under the train. At one point Dickens gave an injured lady who was resting under a tree a sip of brandy. The next time he passed her she was dead. Over the next three hours Dickens did what he could to alleviate people's suffering.

He described the incident in a letter to his friend Mitton:

"My dear Mitton,

I should have written to you yesterday or the day before, if I had been quite up to writing. I am a little shaken, not by the beating and dragging of the carriage in which I was, but by the hard work afterwards in getting out the dying and dead, which was most horrible.

I was in the only carriage that did not go over into the stream. It was caught upon the turn by some of the ruin of the bridge, and hung suspended and balanced in an apparently impossible manner. Two ladies were my fellow passengers; an old one, and a young one. [Author's Note - Dickens conceals the identity of his mistress and her mother] This is exactly what passed:- you may judge from it the precise length of the suspense. Suddenly we were off the rail and beating the ground as the car of a half emptied balloon might. The old lady cried out “My God!” and the young one screamed.

I caught hold of them both (the old lady sat opposite, and the young one on my left) and said: “We can't help ourselves, but we can be quiet and composed. Pray don't cry out.” The old lady immediately answered, “Thank you. Rely upon me. Upon my soul, I will be quiet.” The young lady said in a frantic way, Let us join hands and die friends.” We were then all tilted down together in a corner of the carriage, and stopped. I said to them thereupon: “You may be sure nothing worse can happen. Our danger must be over. Will you remain here without stirring, while I get out of the window?” They both answered quite collectedly, “Yes,” and I got out without the least notion of what had happened.

Fortunately, I got out with great caution and stood upon the step. Looking down, I saw the bridge gone and nothing below me but the line of the rail. Some people in the two other compartments were madly trying to plunge out of the window, and had no idea there was an open swampy field 15 feet down below them and nothing else! The two guards (one with his face cut) were running up and down on the down side of the bridge (which was not torn up) quite wildly. I called out to them “Look at me. Do stop an instant and look at me, and tell me whether you don't know me.” One of them answered, “We know you very well, Mr Dickens.” “Then,” I said, “my good fellow for God's sake give me your key, and send one of those labourers here, and I'll empty this carriage.”

We did it quite safely, by means of a plank or two and when it was done I saw all the rest of the train except the two baggage cars down in the stream. I got into the carriage again for my brandy flask, took off my travelling hat for a basin, climbed down the brickwork, and filled my hat with water. Suddenly I came upon a staggering man covered with blood (I think he must have been flung clean out of his carriage) with such a frightful cut across the skull that I couldn't bear to look at him. I poured some water over his face, and gave him some to drink, and gave him some brandy, and laid him down on the grass, and he said, “I am gone”, and died afterwards.

Then I stumbled over a lady lying on her back against a little pollard tree, with the blood streaming over her face (which was lead colour) in a number of distinct little streams from the head. I asked her if she could swallow a little brandy, and she just nodded, and I gave her some and left her for somebody else. The next time I passed her, she was dead.

Then a man examined at the Inquest yesterday (who evidently had not the least remembrance of what really passed) came running up to me and implored me to help him find his wife, who was afterwards found dead. No imagination can conceive the ruin of the carriages, or the extraordinary weights under which the people were lying, or the complications into which they were twisted up among iron and wood, and mud and water.

I don't want to be examined at the Inquests and I don't want to write about it. It could do no good either way, and I could only seem to speak about myself, which, of course, I would rather not do. I am keeping very quiet here. I have a – I don't know what to call it – constitutional (I suppose) presence of mind, and was not in the least flustered at the time. I instantly remembered that I had the MS of a Novel with me, [Author's Note - Our Mutual Friend] and clambered back into the carriage for it. But in writing these scanty words of recollection, I feel the shake and am obliged to stop.

Ever faithfully,

Charles Dickens

This letter begins to demonstrate the feeatures of PTSD for us - some evidence of anxiety on being reminded of the accidnet adn the start of some avoidance behaviour.

Dickens returned to Gad's Hill Place the day after the accident, and told the landlord of the Falstaff Inn that "I never thought I should be here again", which emphasises that he felt his life had been at risk - a partial diagnostic requirement for PTSD.

His eldest son found that soon after the accident his father was "greatly shaken, though making as light of it as possible -- how greatly shaken I was able to perceive from his continually repeated injunctions to me by and by, as I was driving him in the basket-carriage, to 'go slower, Charley' until we came to foot-pace, and it was still 'go slower, Charley.'" This is suggestive of an initial ‘acute stress reaction’. Further evidence for this acute stress reaction is that even days after the accident he was still overwhelmed by "the shake." He felt weak, experiencing "faint and sick" sensations in his head and he felt nervous.

He wrote letters, in which he mentioned the horrors of the accident and attributes his shakiness not to his work among "the dying and dead..." In the longest letter (to Thomas Mitton), he made it clear that he wanted to avoid being examined at the inquest into the disaster. Sufferers of PTSD often make every effort to avoid thinking or talking about the trauma,

Later when travelling by train (which he again tried to avoid) he suffered from the illusion that his carriage was "down" on the left side. This sounds altogether like a ‘flashback’ or re-living phenomenon as seen in PTSD.

Further avoidance behaviour is evidenced by the fact that travelling became for him a most distressing activity- and this was in man who previously used to relish walking and travelling the length and breadth of the country and lecturing abroad. His international travels ceased.

He tried to overcome his fear of trains by going back in them almost at once (exposure therapy). He had to travel on a slow train rather than the express however, and even the traffic noise of a London carriage distressed him.

Patients with PTSD often lose interest in their usual activities and become withdrawn. After the crash Dickens withdrew from all scheduled public engagements, and "the shake" affected his writing: the rest of that number of Our Mutual Friend, snatched from the crash, was too short.

PTSD can last for years and two years after the crash Dickens wrote that the effect of the Staplehurst accident "tells more and more," A year later he confessed: "I have sudden vague rushes of terror, even when riding in a hansom cab, which are perfectly unreasonable but quite insurmountable."

Dickens's son, Henry, stated that "I have seen him sometimes in a railway carriage when there was a slight jolt. When this happened he was almost in a state of panic and gripped the seat with both hands." And his daughter Mamie recalled that "my father's nerves never really were the same again...we have often seen him, when travelling home from London, suddenly fall into a paroxysm of fear, tremble all over, clutch the arms of the railway carriage, large beads of perspiration standing on his face, and suffer agonies of terror. We never spoke to him, but would touch his hand gently now and then. He had, however, apparently no idea of our presence; he saw nothing for a time but that most awful scene." Dickens often had to leave his train at an early station, and walk the rest of the way home.

His son later said that Dickens 'may be said never to have altogether recovered'. Dickens even died on the fifth anniversary of the Staplehurst disaster.

Copyright Priory Lodge Education Limited 2008

First Published February 2008

Click

on these links to visit our Journals:

Psychiatry

On-Line

Dentistry On-Line | Vet

On-Line | Chest Medicine

On-Line

GP

On-Line | Pharmacy

On-Line | Anaesthesia

On-Line | Medicine

On-Line

Family Medical

Practice On-Line

Home • Journals • Search • Rules for Authors • Submit a Paper • Sponsor us

All pages in this site copyright ©Priory Lodge Education Ltd 1994-